Vol. 3

Photographing the Ancients

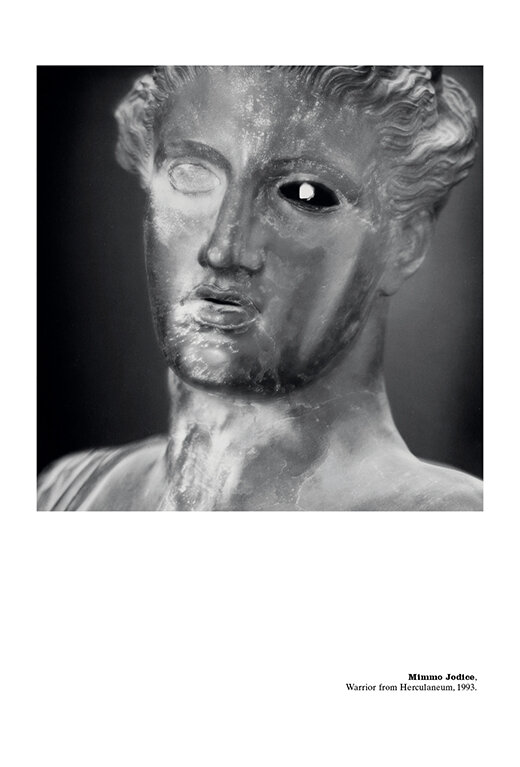

Mimmo Jodice’s Lens on Art and Experience

text by Salvatore Settis | photographs by Mimmo Jodice

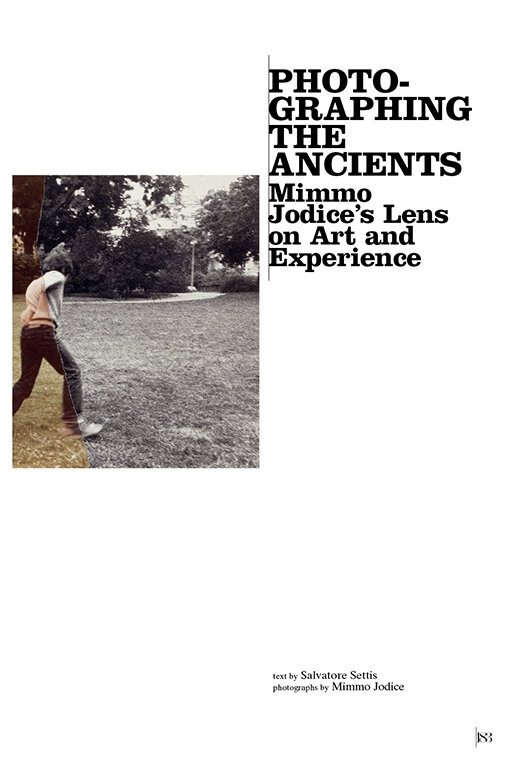

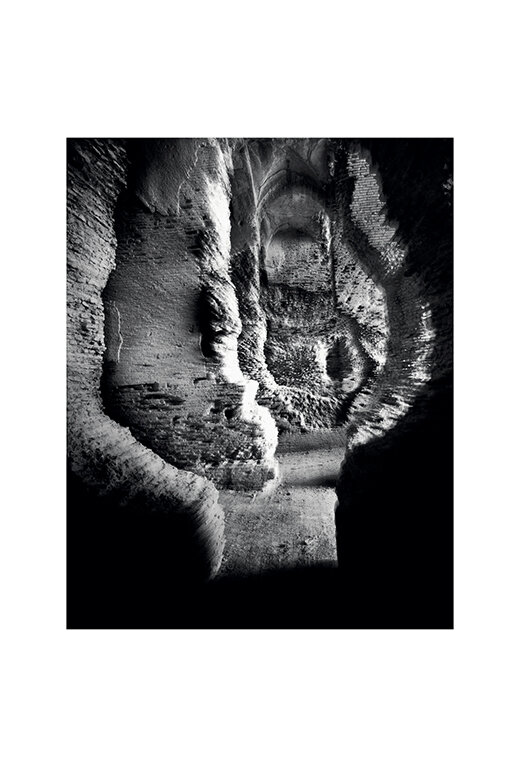

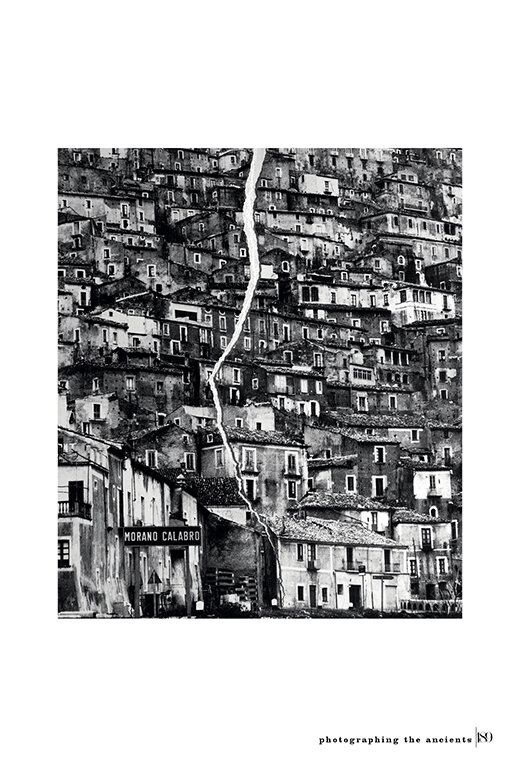

As anthropologists constantly remind us, every social group, and each individual within those groups, is imbued with a specific local knowledge: a mental collection of facts, experiences, images, concepts, perceptions, and convictions that, when assimilated into the environment in which someone grows up and lives, permanently guides their outlook, behaviour, and life choices (see Clifford Geertz’s deservedly famous 1983 book Local Knowledge). One might be tempted to trace Mimmo Jodice’s penchant for photographing Greek and Roman antiquity and Mediterranean landscapes back to a similar starting point, but that would be a mistake. Jodice’s work certainly presupposes his experiences and the environment of his upbringing and adult life in Naples, but he absorbs these and filters them effortlessly through an incisive, intimate knowledge of and familiarity with (or rather, a ruminatio and reconsideration of) the artistic avant-garde of the second half of the twentieth century. For this reason, his vision of the Ionian and Tyrrhenian waves, of the crumbling masonry of Ostia and Pergamon, of the stone and bronze faces of Pompeii and Herculaneum is unusually far-reaching.

It is as if, having chosen photography as the form of expression that best suits him, Jodice interprets all the other art forms of our time as subspecies of photography; or as if, when he grips his camera, he sees it as a draughtsman’s pencil, a painter’s brush, a sculptor’s chisel. Perhaps the process, both technical and artisanal, by which the camera film, once exposed, is manipulated in the darkroom and transfigured into an image worthy of his name, has a hidden association with the ancient coroplasts who modelled clay. In fact, so great is the distance travelled from the simple snapshot recorded by a lens to the final result of the modifications Jodice applies to his negatives that his creative process is perhaps more akin to that of bronze sculpture. In the lost-wax casting process, the statue takes form through adapting to the sculptor’s idea, and it must therefore pass through several successive stages, from the shell model to the terracotta “core”, to the wax coating, to the vented layer of clay, to the final firing and melting, to the cooling and finishing. Similarly, Jodice’s photography involves not only the laborious process of selecting and framing his subjects, but also a searing poetic metamorphosis in which his imagination and craftsmanship manipulate the material, transporting it into his interior realm. And making it ours.